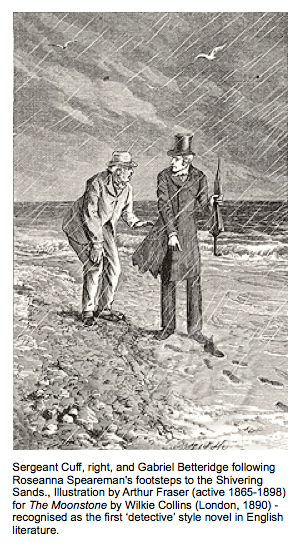

“It looks as if it had hundreds of suffocating people under it—all struggling to get to the surface, and all sinking lower and lower in the dreadful deeps!” The Moonstone, Wilkie Collins, 1868, (1.1.4.39)

In September 2011, I was asked to more clearly define my artistic practice and the methodologies I intended to employ to undertake my research enquiry for my PhD studies.

While vaguely aware from comments heard at various post-graduate seminars that there were difficulties still, with the definition, criteria and evaluation of art-practice PhDs, even though arts practice PhD’s had been around since 1997 (but only since 2006 in Ireland), I felt relatively comfortable with this requirement (which contrasts the many uncertainties I often face with the direction of own artistic practice). After all, no doubt the quality of the enquiry would ultimately rest on the clarity and framework of the aims set out and methodologies employed. My general ease with this proposition was that I have a considerable background in my early working life in scientific research and writing so I imagined that defining the research and outlining the methodologies shouldn’t be too difficult. However, as I was to find, almost most each word in the first sentence that I began this article with now seems uncertain; as shifting, and shivering as Wilkie Collin’s deadly and mysterious quicksand.

The first inkling that this was going to be more challenging than I realised was encountering all the different terms for describing the creative activities of many art forms occurring in a PhD context, and wondering how best my practice and methodologies could, or should be, categorised. I found one could describe one’s creative work as ‘practice-based’, ‘art based’, ‘research-led practice’, ‘artistic research’, ‘creative research’ or even ‘practice-led research’, which initially I strongly agreed with, as without the creative practice work, my enquiry certainly wouldn’t have started.

Perhaps to some it may not appear that important what one calls this type of endeavour, but the more I read, the more I could see the various terms were symptoms of institutions, educators and creative practitioners desperately struggling with the paradox of what a creative PhD was and getting past that, even what it might aspire to be, as distinct from research in other disciplines. The context of these debates were and continue to be taking place in wider debates of the rapid appearance and increase in numbers of creative practice PhDs in many continents. In Europe, debates of creative research at this level appear to be ultimately connected to and shaped by the politics of educational agendas. This is especially thought to be the case with European educational institutes that have adopted the Bolonga European Education directive that relate, some would say negatively, to support free-market economic goals for the European labour market. All of this is also shadowed by the defensive position that the humanities in academia now have to take, facing increasing cutbacks due to the rapid onset of the global economic crisis (Baers, 2011; Biggs and Karlsson, 2011) .

On further examination I found a number of relatively recent publications that offer a sense of the discourse that has and is still developing in defining creative activities at doctoral level. The following publications are listed for two reasons: firstly I wish I had been handed such a list in my first few weeks to more quickly get my bearings in this new territory but also to indicate how recent, still forming and geographically-coloured these debates are. This is by no means a comprehensive list but for a start there is the recent introductory manual, though probably more useful for design practitioners, Creative research: the theory and practice of research for the creative industries by Hilary Collins (2010), a special academic publication titled, Artistic Research in the Series of Philosophy of Art and Art Theory, Vol 18, edited by Annette Balkema and Henk Slager (2004), and other academic books such as Material Thinking by Australian Paul Carter (2004), Practice as Research – Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry edited by Australians Estelle Barret and Barbara Bolt (2004, 2010), Art Practice as Research, Inquiry in Visual Arts (2nd edition) by American Graeme Sullivan which gives a very different perspective on arts education development in the United States (2010), What is research in the Visual Arts? Obsession, Archive and Encounter, ed. by Australians Ann Holly and Marquard Smith (2008) and the large Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts, edited by Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson (2011).

Becoming aware of these politics and debates that surround creative PhD’s goes someway to understanding the current questioning and uncertainty that surrounds activities at this level. Most creative practitioners would probably rightly assume that such a contested arena would be a fatal for their creative work. Yet if one perseveres one can begin to see in the midst of all of the debates and politics, possibilities for re-imagining and re-acknowledging the value and position of the humanities in wider society, though as mentioned previously, there are very real short-term requirements being placed on the humanities to produce more market-valuable, ‘knowledge outcomes’.

As to which term to assign to one’s artistic endeavours? The variety of terms encountered suggests different and contradictory emphasis on different aspects of cultural production. Some terms appear to center on cultural works produced – ‘art-based research’ etc; others, possibly more critically engaged with contemporary art practice discourses, value the the artistic process itself – for example in the term, ‘practice-led’, ‘practice-based’ research. In fact my survey of the previously mentioned texts really helped me to decide how I wanted to frame and present my creative activities. Such reading also made me re-examine the ideas I had gained from science research institute in which I previously worked, an institute that at that time, had became increasingly involved in ‘knowledge outcomes’ to maintain its government core funding. However, while still having considerable respect for scientific endeavours, my own view is that the arts offers a different but equally valid and valuable means of encountering the world than science (or the market economy that has encroached on the sciences) and that terms such as ‘research’, ‘knowledge outcomes’ being place’ or being appropriated for use in creative activities should be adopted with caution.

Similar views are held by some of the contributors of the recent and previously mentioned compendium The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts (2011). For example, Johnson writes a detailed analysis on the distinctions and similarities of scientific and artistic activities drawing on observations by the American philosopher and educational reformer, John Dewey, who emphasised the ‘experiential’ value of art rather than as a system or site of ‘knowledge’ production. Johnson, from Dewey’s writings, argues strongly that art organizes (enacts) a means of ‘feeling’ qualitative experience, one that can both represent and present a unifying quality of ‘knowing’; he stresses it both ‘represents’ and ‘presents’ rather than producing ‘knowledge’ that is associated with other fields of enquiry. While Johnson acknowledges there are qualitative aspects inherent to both artistic and scientific research, he along with others in this text, argues that there is a danger in adopting the terms and models of ’knowledge production and outcomes’ used in science and chiefly favoured by those seeking only the economic returns of research. Johnson promotes that arts practice at this level

would be an enquiry into how to experience and transform the unifying quality of a given experience in search of deepened meaning, enhanced freedom, and increase of connections and relations. Students of art are learning how things are and how they can be reconfigured to change the underlying quality of a certain experience. It is not too grandiose to say that, in their more successful moments, artists help us explore the possibilities of our world, through their grasp of emerging unifying qualities (Johnson, 2011; p. 150-151).

In my own experience, many artists, including myself, often adopt the term ‘research’ as it is so commonly used in everyday life yet by doing so we perhaps unwittingly undermine the unique qualities and values inherent and particular to artistic practice. My own artistic activity is a personal voyage combining ideas and media from various disciplines, coloured by the eco-socio-political contexts in which I live or observe. I would, and do find it difficult, to argue that engaging with ideas about ecology and experimental film in an art and ecology practice will lead to new knowledge; instead I believe that such activities open up a space for myself and my audiences to look and think differently, to re-examine outworn and limiting perspectives and perceptions relating to the earth and its more-than-human inhabitants.

Moreover, there are other considerations in using the word ‘research’. On beginning to survey qualitative methodologies, I again encountered the word ‘research’, but this time it was defined by its history. In the introduction of the third edition of Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Material (2009), Denzin and Lincoln strongly remind all researchers that the word ‘research’ is bound up with colonialism and racism and how research methods were used to scrutinise ‘the Other’ (be it other races or natural resources), to ultimately serve the needs of the white world. For those working in the art and ecology area, one should be mindful that the ‘investigative mentality’ described by Denzin and Lincoln is still dominant in today’s continuing scientific examination of the earth, its species and elements.

At times, definitions of artistic activities may also point to other tensions between artistic practice and orthodox research, where there is often an implicit emphasis that all doctoral activities produce new knowledge. Brown and Sorenson, who have written at length about integrating creative practice and research in the digital media arts in Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts (2009, p.154), argue that art practices uncover knowledge that was previously unknown to the individual but known to the field, while academic research aims at uncovering and creating knowledge that was previously unknown to the field.

To conclude, there is much unsettled territory to navigate when undertaking an artistic PhD. Again referring to the new Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts, leading commentators differ on key definitions of creative doctoral practice as seen in the introductory essay by Helga Nowotny, whose career lies in the social studies of science. Nowotny has argued that artistic practitioners would be well served to more fully adopt the language and methods of scientific research, suggesting that in this way, the arts will take their important place again, alongside the sciences, as in the Renaissance (p. xix). Unfortunately, as pleasing as this might be to imagine, the engines of contemporary society are dominated by the resources directed to science, not to the humanities, a situation that is unlikely to radically change in the near future. Nevertheless, in a world teetering on the brink of resource depletion, widespread species loss and increasing global biosphere instability, independent re-thinking of how we culturally relate to earth systems is essential and urgent.

Just for the record, I will in future be describing my activities as an ‘artistic enquiry’ and will be alert to slipping down too far down into a ‘research’ mentality, thereby, hopefully, avoiding those ‘dreadful deeps’.

Cathy Fitzgerald Dec, 2011

References: to be completed

An interesting post which made me think about my own practise. After i bought the land i wrote down the following poem:

an understanding that

goes beyond

the power of brains

as it connects with senses

that can’t be explained

I wanted to let go dogmatic use of rules and reconnect to the land by using my senses. This intellect is incompatible with the contemporary rationalistic culture in the philosophy of science. A good book to read would be ” Against Method” by Paul Feyerabend.

In 2007 the Biennale di Venezia had as theme: “think with the senses – feel with the mind”. It is this that can connect art with research in my opinion.

The way i started on the land was totally unscientific yet the result is not.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the poem, book title and Venezia theme.

A couple of my favourite authors/green philosophers would be David Abram and Derrick Jensen who also strongly propose thinking with either the senses or looking back to pre-industrial societies relations with their environments. Jensen writes at length about the limitations of scientific thinking. My undergraduate thesis was titled ‘Science and the eclipse of the earth’ so its something I keep circling around, although I’m mindful that science has revealed much too… my close to nature forestry contacts often remark that forestry is both an art and a science.

LikeLike

Brilliant insight to your ‘research’ practice. Thank you for sharing. I would love to post this on Limerick School of Art & Design’s MASPACE.

Deirdre

LikeLike

Thanks so much Deirdre

Of course you can share it but must say my insights into arts practice research methodologies is still not sorted; its still a contested area and very tricky process. Best wishes to you all at MASPACE!

LikeLike

Hi Cathy,

I’d love your permission to re-blog this (providing I can figure out how that’s done).

Moran

LikeLike

Hi Moran

Yes of course but you might want to add that the area is still contested and that Cathy is still working on her methodology, some years later 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Intersecting Interests and commented:

I thought it might be interesting to re-blog the point of view of a colleague on political art/research methodologies. At her request, I’ll add that the area is still contested and that Cathy is still working on her methodology, some years later 🙂

LikeLike